Katelyn Bush

[ About ]

Katelyn Bush is a Memphis native studying English and computer science at Rhodes College. (She knows it's a weird combination.) She is a student writer for The Bridge and a writing tutor. When she's not writing, she's rewatching her favorite TV shows and cooking up new recipes she found on the internet.

[ Contact ]

Email:

[email protected]

[ Writing ]

Cross Cultural Cuisine

An interview with Memphis' "Godfather of Chinese Food", Eddie Pao.

Published in March 2022 issue of The Bridge Newspaper

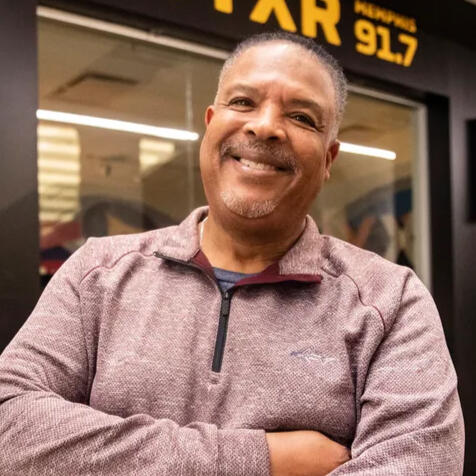

Walking into Mosa felt like stepping back in time. It had been years since my last visit, but the little bistro's lime-green walls and gleaming cherrywood floors looked exactly as I'd remembered them. Soon after my arrival, "Mr. Eddie" Pao emerged from behind a tall counter. He wore his usual attire: a stained black shirt, sleeves rolled up to his elbows, and a matching black cap concealing tufts of greyish-white hair. The skin around his eyes crinkled into a smile as I waved hello. I had called Eddie earlier that day to arrange an interview, and despite my short notice, he graciously agreed to meet me before the dinner rush.

I ordered suan la tang, or hot and sour soup: sliced shiitake mushrooms, peppers, and tofu swimming in a delicate, vinegary broth. Eddie had grown up eating suan la tang in Taipei, and was determined to replicate its signature taste. Aided by his mother, Ying-Chu Pao, he eventually perfected his blend of pungent peppers and savory-sweet spices after months of experimentation.

Eddie’s early life in Taiwan served as inspiration for much of Mosa’s menu. “My best friend’s family owned a beef noodle soup store. Best in the capital of Taiwan. So before I come to the United States, I ask him, ‘Can you teach me?’” Eddie explained–or, more accurately, shouted–over the clatter of pots and pans. “I ate a lot of different kinds of food. Cantonese, Taiwanese, Mandarin– a lot of food on the street, also. I ate everything.” Mosa’s casual fare is reminiscent of Taiwan’s night markets: concentrated clusters of street vendors boasting fatty, fried chicken cutlets and sichuan-style wontons.

Prior to immigrating to America, Eddie was a successful film director. However, Taiwan’s martial law stifled his creative autonomy. “That time in Taiwan, they not allow you to make anything you wanted. No freedom. So I said, ‘Okay, I know the United States is a free country.’ So my sister over here [in the U.S.] applied for immigration for me, and I come with my wife here. At that time, Michelle, my daughter, only eight months old.”

But finding work in America as a director proved futile. “When I go visit the University of Memphis, and even contact the art university in California, they say, ‘Your language makes it a little bit of a problem.’ I said, ‘So what can I do?’ But they say, ‘We see your work and we know you’re a director.’ But they said they cannot help.” Eddie relayed his story with an unfaltering smile, but confessed that he’d love to direct another film someday. When I encouraged him to do so, he simply laughed and responded, “But I think I’m too old.”

Eddie’s wife was the one who suggested he open a restaurant. “Motion picture is for the public. You want a lot of people to watch your movies. And my wife says, ‘If you open a restaurant, you are still helping the public. You love the people, why don’t you try it?’” Eddie agreed, and in 1979, he opened his first restaurant on Summer Avenue. “So I tried it, and now I’m just very lucky. I have a lot of fortune. Memphis people, they accept me– including your dad and mom, coming to eat at my restaurant!” He gestured to me. “We had a full house every day.”

Mosa’s menu borrows from a myriad of Asian cultures. “I read a lot of books that are translated to Chinese, and my manager is Vietnamese,” Eddie explained. “I teach him about Mandarin [food] and he teaches me about Vietnamese. So I learn a lot of new things.” In Mosa’s kitchen, you’ll find a Hispanic chef stir-frying vegetables over a 700-degree wok. Outside, you’ll find guests conversing in Mandarin and Korean sitting next to customers speaking with that classic, sluggish Southern drawl, slurping down bowls of sizzling chow mein noodles. Eddie himself has a hint of country twang in his voice: “[Customers] said my Pad Thai _realllll _good,” he told me. Mosa is more than an outlet for Eddie’s artistic expression; it stitches nationalities together through cuisine. It’s what America prides itself on being: a melting pot of disparate cultures.

A Legacy of Kindness

The community remembers the unparalleled generosity of a Memphis music legend.

Published in February 2022 issue of The Bridge Newspaper

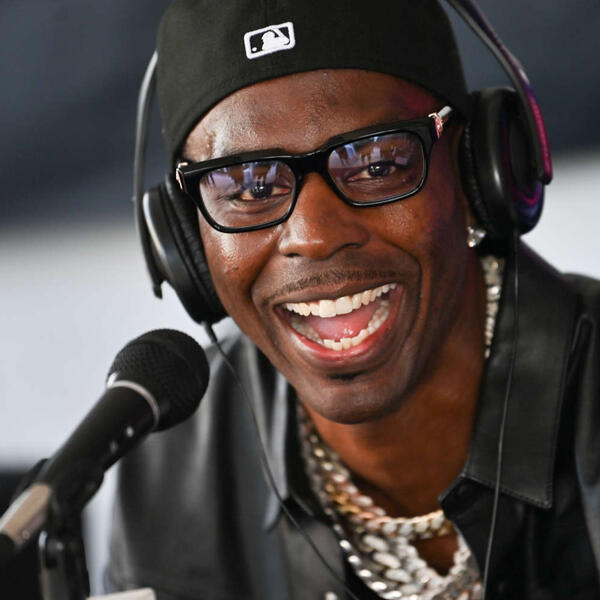

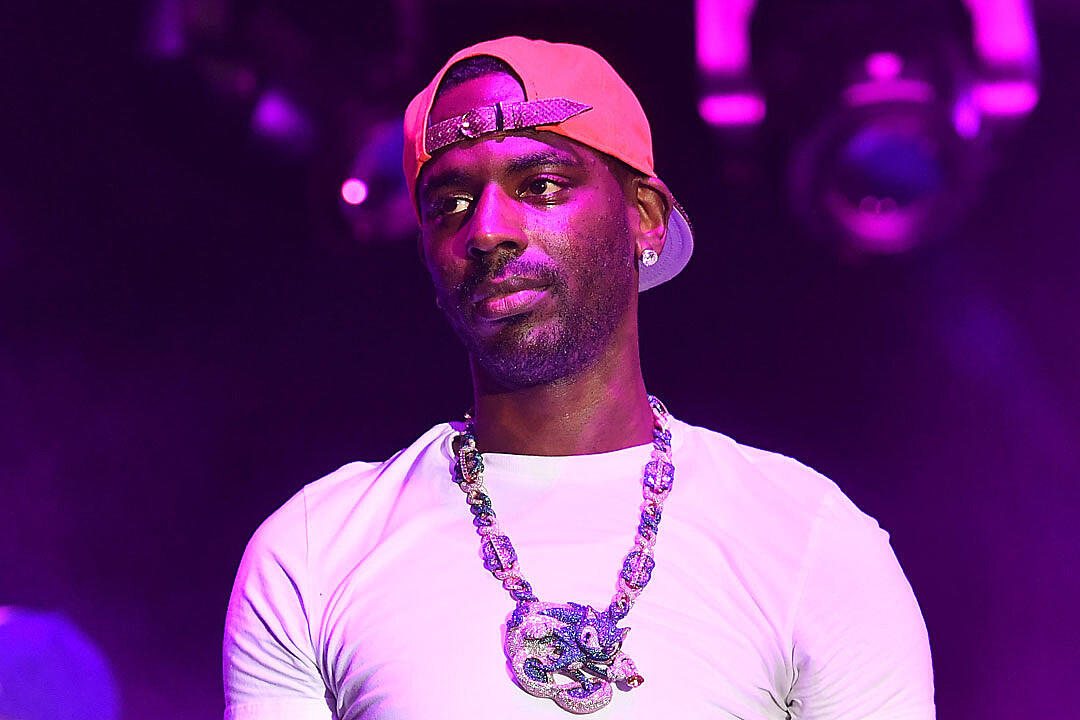

Adolph “Young Dolph” Robert Thornton Jr. was shot to death on November 17th, 2021 outside of his favorite bakery, Makeda’s Butter Cookies. The shop was en route to one of the rapper’s annual “turkey drives”; prior to his death, Young Dolph planned on distributing turkeys to needy families at various community centers throughout Memphis.

But even after his untimely death, the turkey drives went on as scheduled. On December 19th, friends and associates of the rapper worked alongside church volunteers to hand out turkeys, stuffing mix, and cranberry sauce at St. James Missionary Baptist church. “This is what he would want us to do right here, still keep on giving. He came from nothing, but he wanted to make sure everybody got some,” said Bee Bee Jones, Thornton’s label employee and longtime friend.

Young Dolph was no stranger to charity work. Last year, he donated twenty-five thousand dollars to his alma mater, Hamilton High School, for new sports equipment. Through his IdaMae Family Foundation, the hip-hop titan lent a helping hand to vulnerable members of the South Memphis community he grew up in. The non-profit group organized clothing drives for domestic violence victims and financed high school literacy programs, among other things.

Such stories documenting Young Dolph’s uncommon generosity abounded at his public memorial service. Friends and family described him as a man who paid for others’ meals at restaurants, someone who would give the shirt off his back for his fellow Memphians, and above all, a beacon of hope to the city that shaped him. Speakers flew in from Maryland, New York, and Michigan to express their gratitude for the late rapper; R&B legend Monica called him “a bright light that was [shone] upon me.” Perhaps most poignantly, C-Murder sent a video from prison thanking Young Dolph for his companionship: “He gave… to my daughters financially. He talked to me. He checked on me weekly, and the first thing he would ask was how was my spirits. He was truly a thug’s angel.”

Young Dolph’s partner, Mia Jaye, eulogized him in the service’s final moments. “He had a heart of David,” she declared, clutching her son’s hand like a lifeline. Her son added, “My dad trained me to be a good man when I grow up. I’m gonna be the greatest person you’ll ever know.” The crowd roared.

At face value, much of Young Dolph’s discography is materialistic; he was a self-made man, and proud of it. “I turned dirt into diamonds,” he rapped in his distinctive, dark timbre on “Major”. Similarly, his 2015 hit, “Get Paid”, preached the importance of financial independence. But while his music celebrated wealth and fame, Young Dolph maintained his generous spirit until the very end. Tameka Greer, the executive director of Memphis Artists for Change, confirmed that the artist was scheduled to appear at a holiday event for children of incarcerated parents this past December.

In his short lifetime, Young Dolph left an undeniable impact on the city of Memphis. State Senator Katrina Robinson announced a resolution had been passed in honor of the late rapper: November 17th would henceforth be known as “The Young Dolph Day of Service” in Tennessee. But perhaps the clearest evidence of Young Dolph’s impact is the outpouring of love and support for Makeda’s Cookies. The store was badly damaged during the fatal shooting; and outrageously, the bakery’s insurance claim was denied. In response, Memphis activists rallied support for the Black-owned business via Twitter. So far, the cookie shop has received ninety-thousand dollars in donations.

Makeda’s Cookies is also planning to pay homage to Young Dolph by renaming his favorite cookie, the chocolate chip, after him. “There was one thing that Dolph did, [he] use to say when you get off the expressway,” recounted operations manager Raven Winton. “He was like, ‘I can smell y’all. I’m getting off the expressway. I had to come in.’ To know that we’re not going to see that face anymore is… I’m trying to hold back tears.”

During Young Dolph’s memorial service, Reverend Doctor Earle J. Fischer offered words of wisdom to a grieving city. “See, there’s an African proverb that says as long as we speak a person’s name, they shall never die.” Indeed, while Young Dolph’s life was tragically cut short, his legacy of goodness lives on.

What's in a name?

An art installation calls attention to the epidemic of pedestrian deaths in Memphis.

Published in January 2022 issue of The Bridge Newspaper